During an 'in-person' code review at a company, the developer whose code was under review made a comment that got me very curious. It was in regards to these lines of code:

StringBuilder dateList = new StringBuilder();

foreach (string date in lstSelected.Items)

{

dateList.AppendFormat("{0},", date);

}

return dateList.ToString().TrimEnd(',');

Looking at the code, I had to take a moment to understand what it was doing(if it doesn't jump out at you, it is creating a comma delimited list). I had commented that I would prefer using string.Join(",", lstSelected.Items) as it is more concise and readable to me. I also prefer to utilize built in functions whenever possible as I assume the guys at Microsoft are pretty smart and that the utilities they provide are most likely more battle-tested than something I would come up with on my own. My assumption was that this developer was unaware of this utility in the c# library and would be happy to take advantage of it when brought to his attention.

Quite to the contrary, the developer responded that he was used to dealing with buffers and the way he has it is much more efficient and allocates much less memory.

Assuming the developer knew his stuff and wouldn't make such a statement otherwise, I stated that the one line I presented was more readable and the potential efficiencies gained through the developer’s method weren’t worth the loss of readability. This comment was made with the knowledge that this was in a method that would be joining at most 100 strings and wouldn’t be run frequently. The developer however wouldn't budge and I didn't feel it was worth continuing the conversation, so we continued with the code review and went back to our respective workstations.

All that being said though, I was curious. I wanted to try to test the efficiencies or lack thereof regarding string.Join vs. the StringBuilder.

I created two very basic tests. I wanted to launch them both independently while I had some profiler tools running to see if I could notice a difference between the two methods.

[TestClass]

public class UnitTest1

{

List<string> list;

const int NUMBER_OF_STRINGS_TO_JOIN = 1000;

[TestInitialize]

public void Initialize()

{

list = new List<string>();

for (var i = 0; i < NUMBER_OF_STRINGS_TO_JOIN; i++)

{

list.Add(Guid.NewGuid().ToString());

}

}

[TestMethod]

public void TestMethod1()

{

var a = string.Join(",", list);

}

[TestMethod]

public void TestMethod2()

{

var sb = new StringBuilder();

foreach (var item in list)

{

sb.Append(item).Append(",");

}

var a = sb.ToString().TrimEnd(',');

}

}

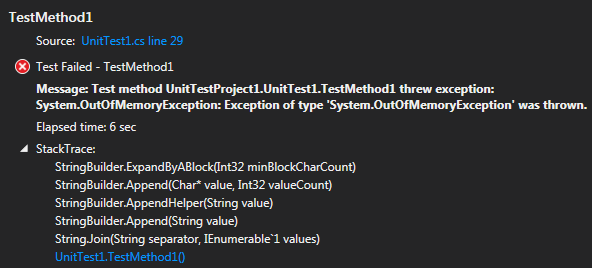

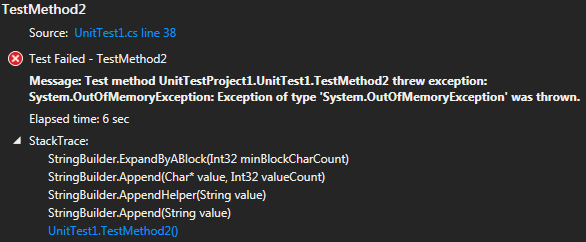

I fired up JetBrains DotMemory and DotTrace to enable some profiling, but as I created the tests and started running them it seemed as though I wasn’t seeing any significant difference between the two methods. I increased the NUMBEROFSTRINGSTOJOIN constant value until I came to 10,000,000. This is where something interesting happened. Both tests failed. I took a screen shot of the test window error messages:

As can be seen from the output of TestMethod1, the method utilizing string.Join, appears as though it uses StringBuilder under the covers.

Comparing this with the output of TestMethod2, I concluded that they were essentially doing the same exact thing. One took one line and was much more readable at a glance while the other consumed 6 lines and took fellow developers a bit more to realize the code's intent.

I shared this with the developer and much to my surprise he still stuck to his guns. I was disappointed by this, but also took the opportunity to remind myself once again that I need to continually be revisiting my coding patterns and practices to see if I really understand what’s going on under the hood. I didn’t know how string.Join was really operating. I don't think we as developers NEED to know how every method we use functions under the covers. When we are presented with an opportunity though, we should utilize it to learn, develop and grow. I was really concerned that not only had I been using, but promoting for a while, a pattern that wasn’t terribly efficient. Now I feel much more comfortable continuing to reuse this pattern and encourage others to do the same. More importantly though, I walked away with a better understanding of one of the myriad tools we as developers utilize on a regular basis. We can't always change those around us, but we can take every opportunity provided to us to encourage our own personal growth as well as those around us.